You Must Be Born Again Serman English Preacher 3000 Times

The Start Bang-up Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept United kingdom and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival motility permanently affected Protestantism every bit adherents strove to renew private piety and religious devotion. The Great Awakening marked the emergence of Anglo-American evangelicalism as a trans-denominational motility inside the Protestant churches. In the U.s., the term Great Awakening is most often used, while in the Uk the movement is referred to every bit the Evangelical Revival.[1]

Building on the foundations of older traditions—Puritanism, Pietism and Presbyterianism—major leaders of the revival such as George Whitefield, John Wesley and Jonathan Edwards articulated a theology of revival and conservancy that transcended denominational boundaries and helped forge a common evangelical identity. Revivalists added to the doctrinal imperatives of Reformation Protestantism an emphasis on providential outpourings of the Holy Spirit. Extemporaneous preaching gave listeners a sense of deep personal conviction of their need of salvation by Jesus Christ and fostered introspection and commitment to a new standard of personal morality. Revival theology stressed that religious conversion was not only intellectual assent to correct Christian doctrine but had to be a "new nativity" experienced in the middle. Revivalists besides taught that receiving assurance of salvation was a normal expectation in the Christian life.

While the Evangelical Revival united evangelicals beyond diverse denominations effectually shared beliefs, it as well led to division in existing churches betwixt those who supported the revivals and those who did not. Opponents accused the revivals of fostering disorder and fanaticism within the churches by enabling uneducated, itinerant preachers and encouraging religious enthusiasm. In England, evangelical Anglicans would grow into an important constituency within the Church of England, and Methodism would develop out of the ministries of Whitefield and Wesley. In the American colonies the Awakening caused the Congregational and Presbyterian churches to split, while it strengthened both the Methodist and Baptist denominations. It had little immediate affect on almost Lutherans, Quakers, and non-Protestants,[two] just afterwards gave ascent to a schism among Quakers (see History of the Quakers) which persists to this day.

Evangelical preachers "sought to include every person in conversion, regardless of gender, race, and status".[iii] Throughout the North American colonies, especially in the South, the revival movement increased the number of African slaves and free blacks who were exposed to and subsequently converted to Christianity.[4] It as well inspired the founding of new missionary societies, such equally the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792.[5]

Continental Europe [edit]

Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom sees the Great Awakening as function of a "corking international Protestant upheaval" that also created pietism in the Lutheran and Reformed churches of continental Europe.[6] Pietism emphasized heartfelt religious faith in reaction to an overly intellectual Protestant scholasticism perceived as spiritually dry. Significantly, the pietists placed less emphasis on traditional doctrinal divisions between Protestant churches, focusing rather on religious experience and angel.[vii]

Pietism prepared Europe for revival, and it usually occurred in areas where pietism was strong. The most important leader of the Awakening in central Europe was Nicolaus Zinzendorf, a Saxon noble who studied under pietist leader August Hermann Francke at Halle University.[viii] In 1722, Zinzendorf invited members of the Moravian Church to live and worship on his estates, establishing a customs at Herrnhut. The Moravians came to Herrnhut equally refugees, just under Zinzendorf'south guidance, the group enjoyed a religious revival. Soon, the customs became a refuge for other Protestants as well, including German Lutherans, Reformed Christians and Anabaptists. The church began to abound, and Moravian societies would be established in England where they would help foster the Evangelical Revival as well.[9]

Evangelical Revival in Britain [edit]

England [edit]

While known as the Slap-up Enkindling in the United States, the motility is referred to every bit the Evangelical Revival in Britain.[1] [10] In England, the major leaders of the Evangelical Revival were three Anglican priests, the brothers John and Charles Wesley and their friend George Whitefield. Together, they founded what would become Methodism. They had been members of a religious lodge at Oxford University called the Holy Society and "Methodists" due to their methodical piety and rigorous asceticism. This society was modeled on the collegia pietatis (jail cell groups) used by pietists for Bible written report, prayer and accountability.[11] [12] All three men experienced a spiritual crisis in which they sought true conversion and assurance of organized religion.[10]

George Whitefield joined the Holy Lodge in 1733 and, under the influence of Charles Wesley, read High german pietist Baronial Hermann Francke'due south Confronting the Fright of Man and Scottish theologian Henry Scougal's The Life of God in the Soul of Man (the latter work was a favorite of Puritans). Scougal wrote that many people mistakenly understood Christianity to be "Orthodox Notions and Opinions" or "external Duties" or "rapturous Heats and extatic Devotion". Rather, Scougal wrote, "True Religion is an Union of the Soul with God . . . It is Christ formed within us."[thirteen] Whitefield wrote that "though I had fasted, watched and prayed, and received the Sacrament long, still I never knew what true religion was" until he read Scougal.[thirteen] From that point on, Whitefield sought the new birth. After a period of spiritual struggle, Whitefield experienced conversion during Lent in 1735.[xiv] [15] In 1736, he began preaching in Bristol and London.[xvi] His preaching attracted large crowds who were drawn to his simple message of the necessity of the new nascence besides as by his manner of delivery. His style was dramatic and his preaching appealed to his audience's emotions. At times, he wept or impersonated Bible characters. By the time he left England for the colony of Georgia in December 1737, Whitefield had become a celebrity.[17]

John Wesley left for Georgia in Oct 1735 to get a missionary for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Wesley made contact with members of the Moravian Church led past Baronial Gottlieb Spangenberg. Wesley was impressed by their organized religion and piety, especially their belief that it was normal for a Christian to have assurance of organized religion. The failure of his mission and encounters with the Moravians led Wesley to question his own faith. He wrote in his journal, "I who went to America to convert others was never myself converted to God."[xviii]

Back in London, Wesley became friends with Moravian minister Peter Boehler and joined a Moravian small grouping chosen the Fetter Lane Society.[19] In May 1738, Wesley attended a Moravian coming together on Aldersgate Street where he felt spiritually transformed during a reading of Martin Luther'south preface to the Epistle to the Romans. Wesley recounted that "I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken abroad my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death."[twenty] Wesley understood his Aldersgate experience to be an evangelical conversion, and information technology provided him with the assurance he had been seeking. Afterwards, he traveled to Herrnhut and met Zinzendorf in person.[19]

John Wesley returned to England in September 1738. Both John and Charles were preaching in London churches. Whitefield stayed in Georgia for three months to plant Bethesda Orphanage before returning to England in Dec.[21] While enjoying success, Whitefield'southward itinerant preaching was controversial. Many pulpits were closed to him, and he had to struggle against Anglicans who opposed the Methodists and the "doctrine of the New Birth". Whitefield wrote of his opponents, "I am fully convinced there is a primal difference between us and them. They believe only an outward Christ, nosotros further believe that He must be inwardly formed in our hearts likewise."[22]

In February 1739, parish priests in Bath and Bristol refused to allow Whitefield to preach in their churches on the grounds that he was a religious enthusiast.[23] In response, he began open up-air field preaching in the mining community of Kingswood, virtually Bristol.[22] Open-air preaching was common in Wales, Scotland and Northern Republic of ireland, but it was unheard of in England. Farther, Whitefield violated protocol by preaching in another priest'south parish without permission.[12] Within a week, he was preaching to crowds of 10,000. Past March, Whitefield had moved on to preach elsewhere. By May, he was preaching to London crowds of 50,000. He left his followers in Bristol in the care of John Wesley.[24] [23] Whitefield's notoriety was increased through the utilise of newspaper advertisements to promote his revivals.[25] Wesley was at first uneasy virtually preaching outdoors, every bit it was contrary to his loftier-church sense of decency. Eventually, however, Wesley inverse his listen, challenge that "all the world [is] my parish".[12] On April two, 1739, Wesley first preached to about 3,000 people near Bristol.[26] From then on he continued to preach wherever he could gather an associates, taking the opportunity to recruit followers to the movement.[27]

Faced with growing evangelistic and pastoral responsibilities, Wesley and Whitefield appointed lay preachers and leaders.[28] Methodist preachers focused particularly on evangelising people who had been "neglected" by the established Church of England. Wesley and his assistant preachers organised the new converts into Methodist societies.[28] These societies were divided into groups called classes—intimate meetings where individuals were encouraged to confess their sins to one some other and to build each other upward. They too took part in beloved feasts which allowed for the sharing of testimony, a fundamental feature of early Methodism.[29] Growth in numbers and increasing hostility impressed upon the revival converts a deep sense of their corporate identity.[28] 3 teachings that Methodists saw every bit the foundation of Christian faith were:

- People are all, by nature, "dead in sin".

- They are "justified past religion alone"

- Faith produces inward and outward holiness.[thirty]

The evangelicals responded vigorously to opposition—both literary criticism and fifty-fifty mob violence[31]—and thrived despite the attacks against them.[31] [32] John Wesley's organisational skills during and later the meridian of revivalism established him every bit the principal founder of the Methodist movement. Past the time of Wesley's decease in 1791, there were an estimated 71,668 Methodists in England and 43,265 in America.[fifteen]

Wales and Scotland [edit]

The Evangelical Revival first broke out in Wales. In 1735, Howell Harris and Daniel Rowland experienced a religious conversion and began preaching to large crowds throughout South Wales. Their preaching initiated the Welsh Methodist revival.[x]

The origins of revivalism in Scotland stretch dorsum to the 1620s.[33] The attempts by the Stuart Kings to impose bishops on the Church of Scotland led to national protests in the class of the Covenanters. In addition, radical Presbyterian clergy held outdoor conventicles throughout southern and western Scotland centering on the communion flavour. These revivals would besides spread to Ulster and featured "marathon extemporaneous preaching and excessive pop enthusiasm."[34] In the 18th century, the Evangelical Revival was led by ministers such every bit Ebenezer Erskine, William Grand'Culloch (the minister who presided over the Cambuslang Piece of work of 1742), and James Robe (minister at Kilsyth).[15] A substantial number of Church of Scotland ministers held evangelical views.[35]

Great Enkindling in North America [edit]

Early revivals [edit]

In the early 18th century, the 13 Colonies were religiously diverse. In New England, the Congregational churches were the established faith; whereas in the religiously tolerant Middle Colonies, the Quakers, Dutch Reformed, Anglican, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Congregational, and Baptist churches all competed with each other on equal terms. In the Southern colonies, the Anglican church was officially established, though in that location were significant numbers of Baptists, Quakers and Presbyterians.[36] At the same time, church membership was depression from having failed to go on upward with population growth, and the influence of Enlightenment rationalism was leading many people to turn to atheism, Deism, Unitarianism and Universalism.[37] The churches in New England had fallen into a "staid and routine ceremonial in which experiential faith had been a reality to but a scattered few."[38]

In response to these trends, ministers influenced by New England Puritanism, Scots-Irish Presbyterianism, and European Pietism began calling for a revival of religion and piety.[37] [39] The blending of these iii traditions would produce an evangelical Protestantism that placed greater importance "on seasons of revival, or outpourings of the Holy Spirit, and on converted sinners experiencing God's love personally."[40] In the 1710s and 1720s, revivals became more frequent among New England Congregationalists.[41] These early revivals remained local diplomacy due to the lack of coverage in impress media. The get-go revival to receive widespread publicity was that precipitated by an convulsion in 1727. As they began to exist publicized more widely, revivals transformed from just local to regional and transatlantic events.[42]

In the 1720s and 1730s, an evangelical party took shape in the Presbyterian churches of the Middle Colonies led by William Tennent, Sr. He established a seminary called the Log College where he trained almost 20 Presbyterian revivalists for the ministry building, including his three sons and Samuel Blair.[43] While pastoring a church in New Jersey, Gilbert Tennent became acquainted with Dutch Reformed government minister Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen. Historian Sydney Ahlstrom described Frelinghuysen as "an important herald, if not the begetter of the Great Enkindling".[43] A pietist, Frelinghuysen believed in the necessity of personal conversion and living a holy life. The revivals he led in the Raritan Valley were "forerunners" of the Bully Awakening in the Heart Colonies. Under Frelinghuysen'southward influence, Tennent came to believe that a definite conversion experience followed by assurance of salvation was the key mark of a Christian. By 1729, Tennent was seeing signs of revival in the Presbyterian churches of New Brunswick and Staten Island. At the same fourth dimension, Gilbert's brothers, William and John, oversaw a revival at Freehold, New Jersey.[44]

Northampton revival [edit]

The most influential evangelical revival was the Northampton revival of 1734–1735 nether the leadership of Congregational minister Jonathan Edwards.[45] In the fall of 1734, Edwards preached a sermon series on justification past religion alone, and the community'southward response was extraordinary. Signs of religious commitment among the laity increased, especially amongst the town's young people. Edwards wrote to Boston minister Benjamin Colman that the town "never was and then full of Dearest, nor then total of Joy, nor so full of distress equally information technology has lately been. ... I never saw the Christian spirit in Honey to Enemies and then exemplified, in all my Life as I take seen it inside this half-twelvemonth."[46] The revival ultimately spread to 25 communities in western Massachusetts and key Connecticut until it began to wane in 1737.[47]

At a time when Enlightenment rationalism and Arminian theology was popular amid some Congregational clergy, Edwards held to traditional Calvinist doctrine. He understood conversion to be the experience of moving from spiritual deadness to joy in the knowledge of ane's ballot (that one had been called by God for salvation). While a Christian might have several conversion moments as part of this process, Edwards believed there was a unmarried point in fourth dimension when God regenerated an individual, fifty-fifty if the exact moment could not exist pinpointed.[48]

The Northampton revival featured instances of what critics called enthusiasm but what supporters believed were signs of the Holy Spirit. Services became more emotional and some people had visions and mystical experiences. Edwards charily dedicated these experiences equally long as they led individuals to a greater belief in God's celebrity rather than in self-glorification. Similar experiences would appear in nearly of the major revivals of the 18th century.[49]

Edwards wrote an account of the Northampton revival, A Faithful Narrative, which was published in England through the efforts of prominent evangelicals John Guyse and Isaac Watts. The publication of his account fabricated Edwards a celebrity in Uk and influenced the growing revival movement in that nation. A Faithful Narrative would become a model on which other revivals would be conducted.[l]

Whitefield, Tennent and Davenport [edit]

George Whitefield first came to America in 1738 to preach in Georgia and institute Bethesda Orphanage. Whitefield returned to the Colonies in November 1739. His first finish was in Philadelphia where he initially preached at Christ Church, Philadelphia's Anglican church, so preached to a large outdoor oversupply from the courthouse steps. He then preached in many Presbyterian churches.[51] From Philadelphia, Whitefield traveled to New York then to the South. In the Middle Colonies, he was popular in the Dutch and German communities as well as among the British. Lutheran pastor Henry Muhlenberg told of a German woman who heard Whitefield preach and, though she spoke no English, later said she had never before been then edified.[52]

In 1740, Whitefield began touring New England. He landed in Newport, Rhode Island, on September 14, 1740, and preached several times in the Anglican church building. He so moved on to Boston, Massachusetts, where he spent a week. There were prayers at King'south Chapel (at the time an Anglican church) and preaching at Brattle Street Church and South Church building.[53] On September 20, Whitefield preached in First Church building and then exterior of it to most eight,000 people who could not gain entrance. The next twenty-four hour period, he preached outdoors again to about 15,000 people.[54] On Tuesday, he preached at Second Church and on Wednesday at Harvard University. Afterward traveling as far as Portsmouth, New Hampshire, he returned to Boston on October 12 to preach to 30,000 people earlier continuing his bout.[53]

Whitefield so traveled to Northampton at the invitation of Jonathan Edwards. He preached twice in the parish church while Edwards was so moved that he wept. He then spent time in New Oasis, Connecticut, where he preached at Yale Academy. From there he traveled down the coast, reaching New York on Oct 29. Whitefield's assessment of New England's churches and clergy prior to his intervention was negative. "I am verily persuaded," he wrote, "the Generality of Preachers talk of an unknown, unfelt Christ. And the Reason why Congregations have been so dead, is considering dead Men preach to them."[53]

Whitefield met Gilbert Tennent on Staten Isle and asked him to preach in Boston to continue the revival in that location. Tennent accepted and in December began a three-month long preaching tour throughout New England. Too Boston, Tennent preached in towns throughout Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. Like Whitefield's, Tennent's preaching produced large crowds, many conversions and much controversy. While antirevivalists such every bit Timothy Cutler heavily criticized Tennent'southward preaching, most of Boston's ministers were supportive.[55]

Tennent was followed in the summertime of 1741 by itinerant minister James Davenport, who proved to be more than controversial than either Tennent or Whitefield. His rants and attacks against "unconverted" ministers inspired much opposition, and he was arrested in Connecticut for violating a law against itinerant preaching. At his trial, he was found mentally ill and deported to Long Isle. Shortly after, he arrived in Boston and resumed his fanatical preaching only to once over again be declared insane and expelled. The last of Davenport's radical episodes took place in March 1743 in New London when he ordered his followers to burn down wigs, cloaks, rings and other vanities. He also ordered the burning of books by religious authors such equally John Flavel and Increment Mather.[55] Following the intervention of two pro-revival "New Lite" ministers, Davenport's mental state apparently improved, and he published a retraction of his before excesses.[56]

Whitefield, Tennent and Davenport would be followed by a number of both clerical and lay itinerants. However, the Enkindling in New England was primarily sustained by the efforts of parish ministers. Sometimes revival would be initiated by regular preaching or the customary pulpit exchanges between two ministers. Through their efforts, New England experienced a "great and general Enkindling" between 1740 and 1743 characterized by a greater interest in religious experience, widespread emotional preaching, and intense emotional reactions accompanying conversion, including fainting and weeping.[56] In that location was a greater emphasis on prayer and devotional reading, and the Puritan ideal of a converted church building membership was revived. It is estimated that between twenty,000 and fifty,000 new members were admitted to New England'due south Congregational churches fifty-fifty as expectations for members increased.[38]

Past 1745, the Enkindling had begun to wane. Revivals would continue to spread to the southern backcountry and slave communities in the 1750s and 1760s.[37]

Conflict [edit]

Philadelphia's Second Presbyterian Church, ministered by New Calorie-free Gilbert Tennent, was built between 1750 and 1753 later on the split between Old and New Side Presbyterians.

The Slap-up Enkindling aggravated existing conflicts inside the Protestant churches, often leading to schisms between supporters of revival, known every bit "New Lights", and opponents of revival, known as "Old Lights". Old Lights saw the religious enthusiasm and itinerant preaching unleashed by the Awakening every bit disruptive to church club, preferring formal worship and a settled, academy-educated ministry. They mocked revivalists as being ignorant, heterodox or con artists. New Lights defendant Onetime Lights of being more concerned with social condition than with saving souls and fifty-fifty questioned whether some Onetime Low-cal ministers were fifty-fifty converted. They as well supported itinerant ministers who disregarded parish boundaries.[37] [57]

Congregationalists in New England experienced 98 schisms, which in Connecticut likewise affected which group would exist considered "official" for revenue enhancement purposes. It is estimated in New England that in the churches there were about i-3rd each of New Lights, Old Lights, and those who saw both sides as valid.[58] The Awakening aroused a moving ridge of separatist feeling inside the Congregational churches of New England. Around 100 Separatist congregations were organized throughout the region by Strict Congregationalists. Objecting to the Halfway Covenant, Strict Congregationalists required evidence of conversion for church building membership and besides objected to the semi–presbyterian Saybrook Platform, which they felt infringed on congregational autonomy. Because they threatened Congregationalist uniformity, the Separatists were persecuted and in Connecticut they were denied the same legal toleration enjoyed past Baptists, Quakers and Anglicans.[59]

The Baptists benefited the most from the Great Enkindling. Numerically small before the outbreak of revival, Baptist churches experienced growth during the terminal half of the 18th century. By 1804, there were over 300 Baptist churches in New England. This growth was primarily due to an influx of old New Calorie-free Congregationalists who became convinced of Baptist doctrines, such every bit believer'due south baptism. In some cases, unabridged Separatist congregations accepted Baptist beliefs.[60]

As revivalism spread through the Presbyterian churches, the Sometime Side–New Side Controversy broke out between the anti-revival "Former Side" and pro-revival "New Side". At result was the place of revivalism in American Presbyterianism, specifically the "relation between doctrinal orthodoxy and experimental cognition of Christ."[51] The New Side, led by Gilbert Tennent and Jonathan Dickinson, believed that strict adherence to orthodoxy was meaningless if one lacked a personal religious experience, a sentiment expressed in Tennent'due south 1739 sermon "The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry building". Whitefield's tour had helped the revival party grow and only worsened the controversy. When the Presbyterian Synod of Philadelphia met in May 1741, the Erstwhile Side expelled the New Side, which so reorganized itself into the Synod of New York.[61]

Aftermath [edit]

Historian John Howard Smith noted that the Great Awakening made sectarianism an essential characteristic of American Christianity.[62] While the Enkindling divided many Protestant churches between Erstwhile and New Lights, it as well unleashed a strong impulse towards interdenominational unity amongst the various Protestant denominations. Evangelicals considered the new birth to be "a bond of fellowship that transcended disagreements on fine points of doctrine and polity", allowing Anglicans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists and others to cooperate across denominational lines.[63]

While divisions between Old and New Lights remained, New Lights became less radical over time and evangelicalism became more than mainstream.[64] [65] By 1758, the Old Side–New Side split in the Presbyterian Church had been healed and the two factions reunited. In part, this was due to the growth of the New Side and the numerical decline of the Quondam Side. In 1741, the pro-revival party had effectually 22 ministers, but this number had increased to 73 by 1758.[66] While the fervor of the Awakening would fade, the acceptance of revivalism and insistence on personal conversion would remain recurring features in 18th and 19th-century Presbyterianism.[67]

The Great Enkindling inspired the cosmos of evangelical educational institutions. In 1746, New Side Presbyterians founded what would become Princeton Academy.[66] In 1754, the efforts of Eleazar Wheelock led to what would become Dartmouth College, originally established to railroad train Native American boys for missionary work amid their own people.[68] While initially resistant, well-established Yale University came to embrace revivalism and played a leading role in American evangelicalism for the next century.[69]

Revival theology [edit]

The Great Enkindling was non the start fourth dimension that Protestant churches had experienced revival; however, it was the first fourth dimension a common evangelical identity had emerged based on a fairly uniform understanding of salvation, preaching the gospel and conversion.[70] Revival theology focused on the manner of conservancy, the stages by which a person receives Christian faith so expresses that organized religion in the way they live.[71]

The major figures of the Great Awakening, such as George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, Gilbert Tennent, Jonathan Dickinson and Samuel Davies, were moderate evangelicals who preached a pietistic form of Calvinism heavily influenced past the Puritan tradition, which held that religion was non only an intellectual exercise simply also had to exist felt and experienced in the heart.[72] This moderate revival theology consisted of a 3-phase procedure. The first stage was conviction of sin, which was spiritual preparation for faith by God'southward law and the ways of grace. The 2d phase was conversion, in which a person experienced spiritual illumination, repentance and faith. The third stage was consolation, which was searching and receiving assurance of conservancy. This process generally took place over an extended time.[73]

Confidence of sin [edit]

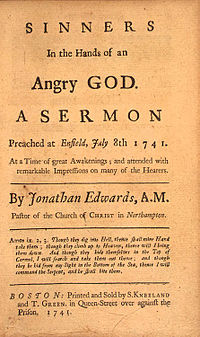

Conviction of sin was the phase that prepared someone to receive salvation, and this stage often lasted weeks or months.[74] When under conviction, nonbelievers realized they were guilty of sin and under divine condemnation and subsequently faced feelings of sorrow and anguish.[75] When revivalists preached, they emphasized God's moral law to highlight the holiness of God and to spark confidence in the unconverted.[76] Jonathan Edwards' sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" is an example of such preaching.[ citation needed ]

As Calvinists, revivalists also preached the doctrines of original sin and unconditional election. Due to the fall of man, humans are naturally inclined to rebel against God and unable to initiate or merit salvation, according to the doctrine of original sin. Unconditional election relates to the doctrine of predestination—that earlier the cosmos of the world God determined who would be saved (the elect) on the footing of his ain choosing. The preaching of these doctrines resulted in the convicted feeling both guilty and totally helpless, since God was in complete control over whether they would be saved or not.[77]

Revivalists counseled those nether conviction to apply the ways of grace to their lives. These were spiritual disciplines such as prayer, Bible report, church attendance and personal moral improvement. While no homo action could produce saving faith, revivalists taught that the ways of grace might brand conversion more than likely.[78]

Revival preaching was controversial amid Calvinists. Because Calvinists believed in election and predestination, some thought it inappropriate to preach to strangers that they could repent and receive salvation. For some, such preaching was only adequate inside their own churches and communities. The revivalists use of "indiscriminate" evangelism—the "do of extending the gospel promises to anybody in their audiences, without stressing that God redeems only those elected for salvation"—was contrary to these notions. While they preached indiscriminately, withal, revivalists connected to affirm Calvinist doctrines of election and predestination.[79]

Another event that had to be addressed were the intense physical and emotional reactions to confidence experienced during the Awakening. Samuel Blair described such responses to his preaching in 1740, "Several would be overcome and fainting; others deeply sobbing, hardly able to contain, others crying in a most dolorous manner, many others more silently weeping. ... And sometimes the soul exercises of some, thought comparatively only very few, would and so far touch on their bodies, as to occasion some strange, unusual bodily motions."[80] Moderate evangelicals took a cautious arroyo to this issue, neither encouraging or discouraging these responses, only they recognized that people might limited their confidence in different ways.[74]

Conversion [edit]

The conviction stage lasted then long considering potential converts were waiting to find evidence of regeneration within their lives. The revivalists believed regeneration or the new nascence was not merely an outward profession of faith or conformity to Christianity. They believed it was an instantaneous, supernatural work of the Holy Spirit providing someone with "a new awareness of the dazzler of Christ, new desires to love God, and a firm delivery to follow God'due south holy constabulary."[74] The reality of regeneration was discerned through self-exam, and while it occurred instantaneously, a convert might only gradually realize it had occurred.[81]

Regeneration was always accompanied by saving faith, repentance and love for God—all aspects of the conversion experience, which typically lasted several days or weeks under the guidance of a trained pastor.[82] True conversion began when the heed opened to a new awareness and honey of the gospel message. Following this illumination, converts placed their faith in Christ, depending on him lone for salvation. At the same time, a hatred of sin and a commitment to eliminate it from the eye would take concord, setting the foundation for a life of repentance or turning away from sin. Revivalists distinguished true conversion (which was motivated by beloved of God and hatred of sin) from false conversion (which was motivated by fright of hell).[83]

Consolation [edit]

True conversion meant that a person was amidst the elect, only fifty-fifty a person with saving faith might doubt his ballot and salvation. Revivalists taught that assurance of salvation was the production of Christian maturity and sanctification.[84] Converts were encouraged to seek assurance through self-examination of their own spiritual progress. The treatise Religious Angel by Jonathan Edwards was written to assist converts examine themselves for the presence of genuine "religious affections" or spiritual desires, such as selfless love of God, certitude in the divine inspiration of the gospel, and other Christian virtues.[85]

Information technology was not enough, however, to simply reflect on past experiences. Revivalists taught that assurance could only be gained through actively seeking to abound in grace and holiness through mortification of sin and utilizing the means of grace. In Religious Affections, the last sign addressed by Edwards was "Christian exercise", and it was this sign to which he gave the near space in his treatise. The search for assurance required conscious attempt on the office of a convert and took months or fifty-fifty years to achieve.[86]

[edit]

Women [edit]

The Awakening played a major office in the lives of women, though they were rarely immune to preach or accept leadership roles.[87] [ page needed ] A deep sense of religious enthusiasm encouraged women, especially to clarify their feelings, share them with other women, and write nearly them. They became more than contained in their decisions, as in the choice of a hubby.[88] This introspection led many women to go along diaries or write memoirs. The autobiography of Hannah Heaton (1721–94), a farm wife of Due north Haven, Connecticut, tells of her experiences in the Great Enkindling, her encounters with Satan, her intellectual and spiritual evolution, and daily life on the farm.[89]

Phillis Wheatley was the get-go published black female poet, and she was converted to Christianity as a child after she was brought to America. Her behavior were overt in her works; she describes the journey of being taken from a Pagan land to be exposed to Christianity in the colonies in a poem entitled "On Being Brought from Africa to America."[90] [ non-primary source needed ] Wheatley became so influenced by the revivals and especially George Whitefield that she dedicated a verse form to him afterwards his death in which she referred to him as an "Impartial Saviour".[91] [ non-primary source needed ] Sarah Osborn adds some other layer to the office of women during the Awakening. She was a Rhode Island schoolteacher, and her writings offer a fascinating glimpse into the spiritual and cultural upheaval of the time period, including a 1743 memoir, various diaries and letters, and her anonymously published The Nature, Certainty and Testify of True Christianity (1753).[92]

African Americans [edit]

The Commencement Great Enkindling led to changes in Americans' agreement of God, themselves, the world around them, and religion. In the southern Tidewater and Low Land, northern Baptist and Methodist preachers converted both white and black people. Some were enslaved at their time of conversion while others were free. Caucasians began to welcome night-skinned individuals into their churches, taking their religious experiences seriously, while also admitting them into active roles in congregations equally exhorters, deacons, and even preachers, although the last was a rarity.[93]

The bulletin of spiritual equality appealed to many enslaved peoples, and, as African religious traditions continued to turn down in North America, Black people accepted Christianity in large numbers for the first time.[94]

Evangelical leaders in the southern colonies had to deal with the issue of slavery much more than frequently than those in the Northward. Still, many leaders of the revivals proclaimed that slaveholders should educate enslaved peoples so that they could become literate and be able to read and written report the Bible. Many Africans were finally provided with some sort of education.[95] [ folio needed ]

George Whitefield's sermons reiterated an egalitarian message, but just translated into a spiritual equality for Africans in the colonies who by and large remained enslaved. Whitefield was known to criticize slaveholders who treated enslaved peoples cruelly and those who did not brainwash them, simply he had no intention to abolish slavery. He lobbied to have slavery reinstated in Georgia and proceeded to become a slave holder himself.[96] Whitefield shared a common belief held amongst evangelicals that, afterward conversion, slaves would exist granted true equality in Sky. Despite his stance on slavery, Whitefield became influential to many Africans.[97]

Samuel Davies was a Presbyterian minister who later became the fourth president of Princeton University.[98] He was noted for preaching to African enslaved peoples who converted to Christianity in unusually big numbers, and is credited with the start sustained proselytization of enslaved peoples in Virginia.[99] Davies wrote a letter in 1757 in which he refers to the religious zeal of an enslaved man whom he had encountered during his journey. "I am a poor slave, brought into a strange country, where I never wait to enjoy my freedom. While I lived in my ain country, I knew nothing of that Jesus I accept heard you speak so much about. I lived quite careless what will become of me when I die; but I now run across such a life will never practise, and I come to you, Sir, that you lot may tell me some good things, apropos Jesus Christ, and my Duty to GOD, for I am resolved not to live whatsoever more than as I have done."[100]

Davies became accustomed to hearing such excitement from many Blackness people who were exposed to the revivals. He believed that Black people could attain knowledge equal to white people if given an adequate didactics, and he promoted the importance for slaveholders to permit enslaved peoples to go literate so that they could get more than familiar with the instructions of the Bible.[101]

The emotional worship of the revivals appealed to many Africans, and African leaders started to sally from the revivals soon after they converted in substantial numbers. These figures paved the way for the establishment of the starting time Black congregations and churches in the American colonies.[102] Before the American Revolution, the first black Baptist churches were founded in the South in Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia; ii Black Baptist churches were founded in Petersburg, Virginia.[103]

Scholarly interpretation [edit]

| | This department needs expansion with: more information on how the Great Awakening has been interpreted by scholars overtime. You can help by adding to it. (Feb 2018) |

The thought of a "great awakening" has been contested by historian Jon Butler as vague and exaggerated. He suggested that historians carelessness the term Cracking Awakening because the 18th-century revivals were only regional events that occurred in only half of the American colonies and their effects on American religion and society were minimal.[104] Historians have debated whether the Enkindling had a political impact on the American Revolution which took identify before long later. Professor Alan Heimert sees a major impact, simply most historians think information technology had merely a small impact.[105] [106]

See besides [edit]

- 2d Slap-up Awakening

- Third Corking Enkindling

- Fourth Great Awakening

- American philosophy

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b Sweeney 2005, p. 186: "'Great Awakening' is a largely American term for the transatlantic revivals of the eighteenth century. British Christians unremarkably refer to the revivals—collectively and more only—as 'the evangelical revival.'"

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, pp. 280–330.

- ^ Taylor 2001, p. 354.

- ^ "Slavery and African American Religion." American Eras. 1997. Encyclopedia.com. (April 10, 2014).

- ^ Bebbington 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 263.

- ^ Campbell 1996, p. 127.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c Bebbington 1989, p. 20.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Smith 2015, p. 110.

- ^ a b Noll 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Sweeney 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Noll 2004, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Noll 2004, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Sweeney 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Noll 2004, p. 97.

- ^ Noll 2004, p. 99.

- ^ a b Kidd 2007, p. 44.

- ^ a b Noll 2004, p. 102.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2015, p. 112.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Hurst, J. F. (1903). "Affiliate IX – Gild and Course". John Wesley the Methodist: a manifestly business relationship of his life and work. New York: Methodist Book Concern.

- ^ a b c Hylson-Smith, Kenneth (1992). Evangelicals in the Church of England 1734–1984. Bloomsbury. pp. 17–21.

- ^ Stutzman, Paul Fike (January 2011). Recovering the Love Feast: Broadening Our Eucharistic Celebrations. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 159. ISBN9781498273176 . Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ John Wesley, The Works of the Reverend John Wesley, A. G. (1831) "A curt history of Methodism," Ii.1. Retrieved on 21 Oct 2016.

- ^ a b Barr, Josiah Henry (1916). Early Methodists nether persecution. Methodist book concern.

- ^ On anti-Methodist literary attacks come across Brett C. McInelly, "Writing the Revival: The Intersections of Methodism and Literature in the Long 18th Century". Literature Compass 12.1 (2015): 12–21; McInelly, Textual Warfare and the Making of Methodism (Oxford Academy Press, 2014).

- ^ Kee et al. 1998, p. 412.

- ^ Smith 2015, p. 70.

- ^ Bebbington 1989, p. 33.

- ^ Smith 2015, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Smith 2015, p. 2.

- ^ a b Ahlstrom 2004, p. 287.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. 30.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. xiv.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Kidd 2007, pp. x–11.

- ^ a b Ahlstrom 2004, p. 269.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 270.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. xiii.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 282.

- ^ Noll 2004, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Kidd 2007, pp. 13–14, 15–sixteen.

- ^ Kidd 2007, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kidd 2007, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b Ahlstrom 2004, p. 271.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 283.

- ^ a b c Ahlstrom 2004, p. 284.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. fourteen.

- ^ a b Ahlstrom 2004, p. 285.

- ^ a b Ahlstrom 2004, p. 286.

- ^ Kidd 2007, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Kee et al. 1998, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 272.

- ^ Smith 2015, p. 8.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 293.

- ^ Smith 2015, p. 3.

- ^ Winiarski 2005.

- ^ a b Ahlstrom 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 275.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 289.

- ^ Ahlstrom 2004, p. 290.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 11.

- ^ Campbell 1996, p. 194.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, pp. 6, 20.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. eight.

- ^ a b c Caldwell 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. xx.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 22.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 30.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 42.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 38.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 39.

- ^ Caldwell 2017, p. 39–41.

- ^ Brekus 1998.

- ^ Matthews 1992, p. 38.

- ^ Lacey 1988.

- ^ Wheatley, Phillis. "On Existence Brought From Africa to America." (London: 1773). Poems Past Phillis Wheatley.

- ^ Wheatley, Phillis. "An Elegiac Verse form On the Death of that historic Divine, and eminent Retainer of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned Mr. George Whitefield." (London: 1773). Massachusetts Historical Social club.

- ^ Brekus 2013.

- ^ Kidd 2008, p. xix.

- ^ Lambert 2002.

- ^ Butler 1990.

- ^ Whitefield, George. To the Inhabitants of Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina (Philadelphia: 1740); quoted in Kidd 2008, pp. 112–115

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. 217.

- ^ Presidents of Princeton from princeton.edu. Retrieved Apr 8, 2012.

- ^ "Samuel Davies and the Transatlantic Campaign for Slave Literacy in Virginia," Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine an abridged version of Jeffrey H. Richards' article. from historicpolegreen.org. Retrieved April eight, 2012.

- ^ Letters from the Reverend Samuel Davies (London, 1757), p. 19.

- ^ Lambert 2002, p. xiv.

- ^ Butler, Wacker & Balmer 2003, p. 112–113.

- ^ Brooks 2000.

- ^ Butler 1982, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Heimert 1966.

- ^ Goff & Heimert 1998.

Bibliography [edit]

- Ahlstrom, Sydney E. (2004) [1972]. A Religious History of the American People (2d ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN0-385-11164-9.

- Bebbington, David W. (1989). Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s. Routledge. ISBN0-415-10464-five.

- Brekus, Catherine A. (1998). Strangers & Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845. Academy of North Carolina Press. ISBN9780807824412.

- Brekus, Catherine A. (2013). Sarah Osborn'south World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early on America. Yale Academy Press. ISBN9780300188325.

- Brooks, Walter Henderson (2000) [1910]. The Silver Bluff Church building: A History of Negro Baptist Churches in America (electronic ed.). Academy of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Butler, Jon (September 1982). "Enthusiasm Described and Decried: The Great Awakening as Interpretative Fiction". Periodical of American History. 69 (2): 305–325. doi:10.2307/1893821. JSTOR 1893821.

- Butler, Jon (1990). Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People . Studies in Cultural History. Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0674056015.

- Butler, Jon; Wacker, Grant; Balmer, Randall (2003). Religion in American Life: A Short History. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0199832699.

- Caldwell, Robert W., III (2017). Theologies of the American Revivalists: From Whitefield to Finney. InterVarsity Press. ISBN9780830851645.

- Campbell, Ted A. (1996). Christian Confessions: A Historical Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN9780664256500.

- Goff, Philip; Heimert, Alan (December 1998). "Revivals and Revolution: Historiographic Turns since Alan Heimert's Religion and the American Mind". Church building History. 67 (four): 695–721. doi:10.2307/3169849. JSTOR 3169849.

- Heimert, Alan (1966). Religion and the American Mind: From the Corking Awakening to the Revolution . Harvard University Printing.

- Kee, Howard C.; Frost, Jerry W.; Albu, Emily; Lindberg, Carter; Robert, Dana Fifty. (1998). Christianity: A Social and Cultural History (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN0135780713.

- Kidd, Thomas S. (2007). The Great Enkindling: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America. Yale Academy Press. ISBN978-0-300-11887-two.

- Kidd, Thomas South. (2008). The Great Awakening: A Cursory History with Documents. Bedford Series in History and Culture. Bedford/ St. Martin's. ISBN9780312452254.

- Lacey, Barbara E. (Apr 1988). "The World of Hannah Heaton: The Autobiography of an Eighteenth-Century Connecticut Subcontract Woman". William and Mary Quarterly. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Civilisation. 45 (2): 280–304. doi:10.2307/1922328. JSTOR 1922328.

- Lambert, Frank (Winter 2002). "'I Saw the Book Talk': Slave Readings of the First Bully Enkindling". The Journal of African American History. 87 (i): 12–25. doi:10.1086/JAAHv87n1p12. JSTOR 1562488.

- Matthews, Glenna (1992). The Rising of Public Adult female: Woman'due south Power and Adult female'south Place in the United States, 1630–1970. Oxford University Printing. ISBN9780199951314.

- Noll, Mark A. (2004), The Ascension of Evangelicalism: The Historic period of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys, Inter-Varsity, ISBN1-84474-001-3

- Smith, Howard John (2015). The First Great Awakening: Redefining Faith in British America, 1725–1775. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN978-i-61147-714-6.

- Stout, Harry (1991). The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism. Library of Religious Biography. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN9780802801548.

- Sweeney, Douglas A. (2005). The American Evangelical Story: A History of the Movement . Bakery Academic. ISBN978-ane-58558-382-9.

- Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies: The Settling of Northward America. Penguin Books. ISBN9780142002100.

- Winiarski, Douglas L. (2005). "Jonathan Edwards, Enthusiast? Radical Revivalism and the Great Awakening in the Connecticut Valley". Church building History. 74 (4): 683–739. doi:10.1017/s0009640700100861. JSTOR 27644661.

Further reading [edit]

Scholarly studies [edit]

- Bonomi, Patricia U. Under the Cope of Sky: Faith, Society, and Politics in Colonial America Oxford University Press, 1988

- Bumsted, J. M. "What Must I Do to Be Saved?": The Great Awakening in Colonial America 1976, Thomson Publishing, ISBN 0-03-086651-0.

- Choiński, Michał. The Rhetoric of the Revival: The Language of the Bully Enkindling Preachers. 2016, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 978-three-525-56023-5.

- Conforti, Joseph A. Jonathan Edwards, Religious Tradition and American Culture University of North Carolina Press. 1995.

- Fisher, Linford D. The Indian Keen Enkindling: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Gaustad, Edwin Southward. The Great Enkindling in New England (1957)

- Gaustad, Edwin S. "The Theological Effects of the Swell Awakening in New England," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 40, No. 4. (Mar., 1954), pp. 681–706. JSTOR 1895863.

- Goen, C. C. Revivalism and Separatism in New England, 1740–1800: Strict Congregationalists and Separate Baptists in the Bang-up Awakening 1987, Wesleyan University Printing, ISBN 0-8195-6133-9.

- Hatch, Nathan O. The Democratization of American Christianity 1989.

- Isaac, Rhys. The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790 1982, emphasis on Baptists

- Kidd, Thomas Due south. God of Freedom: A Religious History of the American Revolution (2010).

- Lambert, Frank. Pedlar in Divinity: George Whitefield and the Transatlantic Revivals; (1994)

- Lambert, Frank. "The First Not bad Awakening: Whose interpretive fiction?" The New England Quarterly, vol.68, no.4, pp. 650, 1995

- Lambert, Frank. Inventing the "Great Enkindling" (1998).

- McLoughlin, William G. Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America, 1607–1977 (1978).

- Schmidt, Leigh Eric. Holy Fairs: Scotland and the Making of American Revivalism (2001)

- Schmotter, James W. "The Irony of Clerical Professionalism: New England's Congregational Ministers and the Swell Awakening", American Quarterly, 31 (1979), a statistical study JSTOR 2712305

- Smith, John Howard. The Beginning Groovy Awakening: Redefining Religion in British America, 1725–1775 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015) ISBN 978-1611477160

- Smith, Lisa. The First Great Awakening in Colonial American Newspapers: A Shifting Story (2012)

- Ward, Westward. R. (2002). The Protestant Evangelical Enkindling. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN0521892325. .

- Winiarski, Douglas L. Darkness Falls on the Land of Low-cal: Experiencing Religious Awakenings in Eighteenth-Century New England (U of North Carolina Press, 2017). xxiv, 607 pp.

Historiography [edit]

- McLoughlin, William Chiliad. "Essay Review: the American Revolution equally a Religious Revival: 'The Millennium in One Land.'" New England Quarterly 1967 40(1): 99–110. JSTOR 363855

Principal sources [edit]

- Jonathan Edwards, (C. Goen, editor) The Peachy-Enkindling: A True-blue Narrative Collected contemporary comments and letters; 1972, Yale Academy Printing, ISBN 0-300-01437-6.

- Alan Heimert and Perry Miller ed.; The Great Awakening: Documents Illustrating the Crisis and Its Consequences 1967

- Davies, Samuel. Sermons on Of import Subjects. Edited past Albert Barnes. 3 vols. 1845. reprint 1967

- Gillies, John. Memoirs of Rev. George Whitefield. New Haven, CN: Whitmore and Buckingham, and H. Mansfield, 1834.

- Jarratt, Devereux. The Life of the Reverend Devereux Jarratt. Religion in America, ed. Edwin S. Gaustad. New York, Arno, 1969.

- Whitefield, George. George Whitefield's Journals. Edited past Iain Murray. London: Banner of Truth Trust, 1960.

- Whitefield, George. Letters of George Whitefield. Edited by S. Chiliad. Houghton. Edinburgh, UK: Banner of Truth Trust, 1976.

External links [edit]

- Lesson program on Start Great Awakening

- The Great Awakening Comes to Weathersfield, Connecticut: Nathan Cole'south Spiritual Travels

- "I Believe It Is Because I Am a Poor Indian": Samsom Occom's Life as an Indian Minister

- "The Joseph Bellamy House: The Not bad Enkindling in Puritan New England", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Edwards, "Sinners in the Easily of an Angry God" text

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Great_Awakening

0 Response to "You Must Be Born Again Serman English Preacher 3000 Times"

Enregistrer un commentaire